Transforming recursive Algorithms into iterative loops (in Oberon)

TL;DR

Some years ago, I was trying to wrap my head around how to transform

recursions into iterative loops. The way to go would be transforming

typical recursions (e.g. derived from mathematical definitions) into

tail-call recursions, which can then easily be expressed as loops. The

harder part (especially when more than one recursion call is involved) is

the transformation into a tail call recursion, which can be done using

continuation passing. Motivation was, besides avoiding stack

overflows, to gain a better understanding of the properties of

recursive algorithms. I was doing this using Oberon (With's object

oriented successor to Pascal), which I think until today is one of

the languages most suitable for expressing readable algorithms.

Besides that, it seems still worthy to learn from these experiments

when e.g. programming in python.

The fibonacci sequence

The fibonacci sequence is a classical example of a sequence defined in terms of recursion.

- f1 = f2 = 1

- fn = fn-2 + fn-1

It also can be expressed easily in an iterative way:

- (fa, fb) := (1, 1)

- (fa, fb) := (fb, fa + fb)

- repeat step 2 until requested number reached

While this can be formulated as a simple tail call recursion quite nicely, I was more interested in the first definition, as it's properties are more similar to those of recursive algorithms traversing binary trees, for example.

In Oberon, it looks like this:

PROCEDURE fib(n:INTEGER): INTEGER; VAR result: INTEGER; BEGIN IF n < 2 THEN result := 1 ELSE result := fib(n-2) + fib(n-1) END RETURN result END fib;

As a remark, in Oberon-07 the RETURN statement is a special

statement only applicable at the end of a function. This is to

explicitly express there are no premature exits from the function

procedure. While this sometimes demands the declaration of a local result

variable in program code, it actually can be removed by an

optimizing compiler.

The fibonacci function can be embedded into a module like this:

MODULE Recursion;

IMPORT Out;

PROCEDURE fib(n:INTEGER): INTEGER;

(* implementation *)

END fib;

PROCEDURE Test*; (* Recursion.Test *)

VAR i: INTEGER;

BEGIN

FOR i := 1 TO 35 DO

Out.WriteInt(i, 4); Out.WriteString(": ");

Out.WriteInt(fib(i), 4); Out.WriteLn

END

END Test;

END Recursion.

In an Oberon System, the Test procedure (declared as exported from the

module by the asterisk) could then be executed by just clicking on the text

Recursion.Test within the comment marks. Don't be disturbed too much

by the very pascalesque style of the Write statements (and also not by

the style of putting more than one statement into a single line..)

Tail call recursion with continuations

In the next step, the simple recursive procedure is transformed into a tail call recursion, involving a result variable taken through the recursion, accumulating the intermediate result steps. As there are two recursive calls, this is done by using continuations.

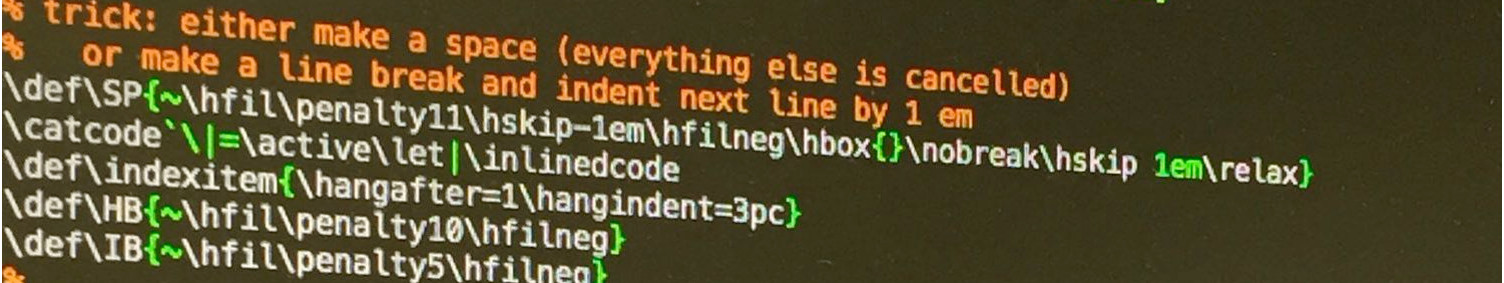

First, we define three classes (and a common base class) containing the data of the different continuation steps and the respective constructor procedures.

TYPE

Continuation = POINTER TO ContinuationDesc;

ContinuationDesc = RECORD END;

Ident = POINTER TO IdentDesc;

IdentDesc = RECORD(ContinuationDesc) END;

P1 = POINTER TO P1Desc;

P1Desc = RECORD(ContinuationDesc)

n: INTEGER;

cont: Continuation

END;

P2 = POINTER TO P2Desc;

P2Desc = RECORD(ContinuationDesc)

res1: INTEGER;

prev: P1

END;

PROCEDURE ident(): Continuation;

VAR result: Ident;

BEGIN NEW(result)

RETURN result END ident;

PROCEDURE step1(n: INTEGER; cont: Continuation): Continuation;

VAR result: P1;

BEGIN NEW(result); result.n := n; result.cont := cont

RETURN result END step1;

PROCEDURE step2(res1: INTEGER; prev: P1): Continuation;

VAR result: P2;

BEGIN NEW(result); result.res1 := res1; result.prev := prev

RETURN result END step2;

The fibonacci function now needs a few embedded helper

functions for the continuations. This actually could be expressed much

more condensed if there were anonymous lambda functions and closures of

local variable environments in Oberon. On the other hand, this

explicit formulation of procedures in my opinion expresses more clearly the

different steps involved. Also note in Oberon the CASE

statement is actually a type dispatcher.

PROCEDURE fib(n:INTEGER; cont: Continuation): INTEGER;

VAR result: INTEGER;

PROCEDURE dispatch(cont: Continuation; value: INTEGER): INTEGER;

VAR result: INTEGER;

PROCEDURE Step1(closure: P1; res1: INTEGER): INTEGER;

BEGIN RETURN fib(closure.n-1, step2(res1, closure))

END Step1;

PROCEDURE Step2(closure: P2; res2: INTEGER): INTEGER;

BEGIN RETURN dispatch(closure.prev.cont, closure.res1 + res2)

END Step2;

BEGIN

CASE cont OF

Ident: result := value |

P1: result := Step1(cont, value) |

P2: result := Step2(cont, value)

END

RETURN result END dispatch;

BEGIN

IF n < 2 THEN result := dispatch(cont, 1)

ELSE result := fib(n-2, step1(n, cont)) END

RETURN result END fib;

What this code says is

- if n < 2, don't return the result value of 1, but dispatch it to the current continuation object,

- else do a recursive call of fib with n-2, forwarding it's

result to a

P1continuation object generated by the step1 procedure.

So far, now we have just one tail call recursion. Later on, when such

a P1 continuation is dispatched, it will do the second recursive

call of fib, this time with n-1 and forwarding that call's result to a

P2 continuation object, which also receives the result of the first

call. Again later on, when dispatching that P2 object, the two intermediate

results forwarded from the previous calls with n-2 and n-1 are added

and the final result is dispatched to the stored initial continuation.

Finally, the initial call to fib in the Test procedure is changed to

Out.WriteInt(fib(i, ident()), 4);. This way, the continuation object

receiving the final result when dispatched will just return it.

As you see, this involves quite a few bits of glue code, some of which is going away again in the next step.

Iterative approach

Now, each tail call recursion is nothing else than a loop with the parameter variable values replaced by the arguments of the recursion call. We now do this transformation into a loop in two steps. First, if you have a closer look, you see there actually is an inner (tail call) recursion in the dispatch function.

PROCEDURE fib(n:INTEGER; cont: Continuation): INTEGER;

VAR result: INTEGER;

PROCEDURE dispatch(cont: Continuation; result: INTEGER): INTEGER;

VAR

closure: Continuation;

done: BOOLEAN;

BEGIN done := FALSE;

REPEAT

closure := cont;

CASE closure OF

Ident: done := TRUE |

P1: result := fib(closure.n-1, step2(result, closure)); done := TRUE |

P2: INC(result, closure.res1); cont := closure.prev.cont;

END

UNTIL done

RETURN result END dispatch;

BEGIN

IF n < 2 THEN result := dispatch(cont, 1)

ELSE result := fib(n-2, step1(n, cont)) END

RETURN result END fib;

Now, the dispatch function contains a loop and the two helper

functions are gone. In case of dispatching a P1 object, as before,

we return the result of the recursive fib call and leave the loop. In

case of the Ident object, the loop is also left and we just route

through the result passed in.

P2 objects are dispatched now by adding their intermediate result to

our result variable, taking their continuation object as our next one

and then repeating, which is exactly what the recursive dispatch call

in the previous version did (if the Oberon compiler could do tail call

optimization).

Iterative approach, continued

Finally, we also transform the outer recursion into a loop, combining

it with the dispatcher loop into a multi-headed WHILE, which again is

a specialty of Oberon.

PROCEDURE fib(n:INTEGER; cont: Continuation): INTEGER;

VAR

closure: Continuation;

result: INTEGER;

BEGIN result := 1;

WHILE n >= 2 DO

cont := step1(n, cont); DEC(n, 2)

ELSIF ~(cont IS Ident) DO

closure := cont;

CASE closure OF

P1: cont := step2(result, closure); n := closure.n-1; result := 1 |

P2: INC(result, closure.res1); cont := closure.prev.cont;

END

END

RETURN result END fib;

While this looks totally non-intuitive compared to the original simple recursion, it shows how a recursion with more than one recursive call can be implemented as a loop.

Final thoughts

When thinking about this, you see the growing stack involved in the original recursion actually being replaced by a growing structure of objects dynamically allocated in memory. In the recursive case, the stack is unfolded by leaving recursion levels, while in the iteration, the garbage collector is involved, cleaning up abandoned objects.

When using the original Oberon system with cooperative multitasking, you could now do further rewrites involving oberon tasks, breaking down the loop into task steps to allow the garbage collector to kick in between.

You could also replace the dynamically allocated objects by using a static array of objects in form of an explicit stack. When doing this you might find some interesting peculiarities, like the maximum array size needed for this being n-1, which is obvious if you think about this recursion a little bit ;-)

If you like, leave a comment on Reddit.